One of the things I love most about my job is the opportunity to design a workplace that is dynamic, progressive, and innovative. We’re taking a fresh look across all of our people practices, trying to improve many of the things that most companies take for granted. We often find ourselves asking employees and prospective employees to re-think their existing notions of what work looks like.

No topic has produced more conversation and debate for us within Blend than titles. Yes, those words we use to describe what we do and where we sit in our organization. Our CEO, Nima Ghamsari, already had a pretty strong point-of-view on titles when I joined Blend 18 months ago. His view: titles are often poorly implemented, often misrepresentative, and almost always dangerous to the culture as a result.

Blend is a purpose-driven and principles-based organization. Two of our principles focus on transparency and impact (read: meritocracy). While these particular principles are common among tech companies, in practice they are almost always impossible to achieve.

Let’s start with how companies work: companies are made up of people, and the best companies are made up of the most ambitious people. Those ambitious people want recognition and reward for their accomplishments. One of the ways traditional organizations reward people is with no additional salary, no additional equity, no additional responsibility — but with an honorary title given to keep someone satisfied or help them appear important to the outside world. As a senior-level candidate I was interviewing recently said to me, “titles are cheap.” In the abstract, this all seems harmless, but in the real world, it has implications.

Years ago, I had an experience scaling a multinational corporation. The company had not been very thoughtful about titling, and so there were pretty big inequities across the organization. In particular, we were guilty of what was described above: we gave honorary titles to people that didn’t reflect their responsibility in the organization. Client-facing employees felt they needed a Vice President title to help close deals. As we gave the title to some, others on the team felt they should also get that title – after all, they had also helped grow our client base. They were cheap, so we gave it to them.

It all came to a head at a leadership summit we were putting together. We wanted to bring together a group of the leaders with the most responsibility to discuss corporate strategy. In order to be “fair”, we started by inviting all Vice Presidents across the company — there were 30 or 40 in all, and three-quarters of those were in Sales. The room, and thus the discussion, was tilted toward sales, while our engineering and product organizations had almost zero representation. This lack of consistency made it really hard to understand whose job was a “real” VP role, and whose job was only about their outward appearance to clients. Is it okay to tell someone they’re a “fake VP”? This too was a principles-based company, and suddenly I realized how important something as simple as titling is to get right. This company had not taken a deliberate, principles-based approach to something so important. And now, as we scaled, it was really hard to put that genie back in the bottle.

This experience and many others led for myself and Nima, to create a few guiding principles for our approach to titles:

Titles ought to be descriptive and consistent

When I hired an internal communications person on my team, her title was “Internal Communicator.” That title actually tells people what she does. I considered calling her an Internal Communications Specialist — but I don’t know what that means, and so we got really focused on highly descriptive titles. Our rule of thumb: someone should be able to, at a glance, know exactly where someone sits in the organization and their scope of responsibility by reading their title.

Honorific titles are counterproductive

Nima and I both had troubling experiences with “honorific” titles that didn’t explain what you did and only served to allow the company to “compensate” the employee instead of actual monetary recognition like more salary or equity. If we want to recognize someone’s growth and performance, we give them more compensation and responsibility. If that changes where they sit in the organization, that may change their title, but also may not.

Titles & compensation should not be tied to each other

As mentioned above, a title ought to represent what you do and where you sit in the organizational structure, not how valuable you are. Tying the two together produces unintended effects when you want to make changes. Decoupling titles and compensation enables us to compensate solely based on value, not hierarchy. In fact, this has been critical in enabling Blend to have highly compensated non-management tracks that are equivalent in compensation to the management tracks.

Ambition for titles is misguided

We’ve all been socialized to be ambitious for titles. But, at Blend, we believe that all a title ought to do is represent your place in the organization. We have to re-train ourselves to think of career growth differently – and focus on the impact we have.

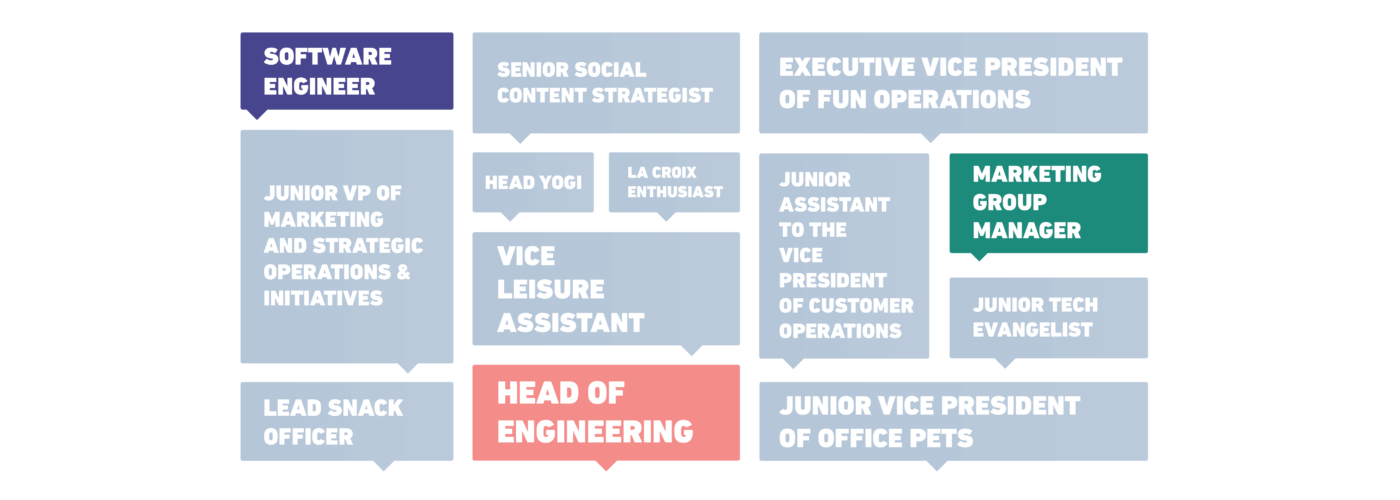

The results of these principles mean that at Blend, your title always includes your specific functional responsibility (e.g., Engineering, Product Management, Sales), often ending with additional descriptors (“Business Development, Alliances”) to ensure absolute clarity about your role.

If you manage people, your title begins with either:

- “Manager” (you manage individual contributors),

- “Group Manager” (you manage at least one manager), or

- “Head” (you report to the CEO) depending on where you sit within the organization.

These are not “permanent” titles — should your situation change (you go from managing managers to individual contributors, for instance), your title will change to reflect that.

There are, of course, downsides to this approach. The first is the recognition employees expect to receive when they get promoted to a new level. Advisors constantly tell me that millennials want and “need” lots of promotions to feel better. I hear that, but I think that’s too simplistic. I think what they really want is to have some sense of a level playing field, and an opportunity to grow and take on more, and to earn. We offer all of that at Blend, in return for a slightly different take on what we call you.

The other issue is at the other end of the titling structure. We’re in growth mode right now and hiring senior-level people and asking them to come in and take a “lower” title is not always easy. But, as Nima points out, if they are really that hung up on the title then they probably are not the best fit for us, and vice-versa. We’re focused on job content, compensation, and performance — not level or title.

The final argument that we’ve had to work through is how we’re setting employees up for their next role. And it’s one we take seriously — development is at the core of our talent strategy. Unfortunately, titles are not consistent across our industry or any other. There are VPs and Directors at some companies who have very little responsibility and compensation, while there are some “managers” (at a company like Facebook) who manage massive functions. If an employer is hiring someone solely based on a title from a previous role, they will end up making bad decisions. Not only does this short-cutting of the selection process produce bad results for the company, it also will continue to skew toward traditional models of success, producing bad outcomes for companies that are actively investing in diversity and inclusion.

One of my favorite of our principles is that we are not afraid to take the road less traveled if it’s the right thing for Blend. And I think that titling, for us, may be a road less traveled, but one that I think will serve us well into the future. Making Blend an equitable, fair and high-performing organization starts with a really clear perspective on roles, responsibilities and what’s important. For us, always, what’s important is value creation and impact, not what we call you.